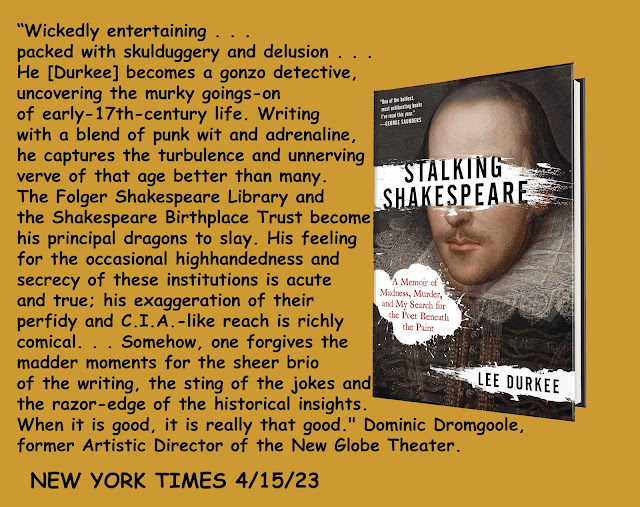

Left: portrait known as David Rizzio (Royal Collection,

artist unknown, image from Wikicommons). Right: the Droeshout engraving

from Shakespeare's 1623 First Folio (artist unknown, image from Folger Shakespeare Library).

The Droeshout engraving is our only authenticated portrait of the poet.

For centuries now scholars have been searching for the presumed ad

vivum (from life) painted portrait used to create this world famous engraving.

Note 1: there is a very intriguing update at the bottom of this post.

Note 2: all images in this post are being used under fair-use laws. This is an argument regarding the possible mis-identification of a historical portrait that might be connected to William Shakespeare.

If

I were allowed to choose one portrait from the Royal Collection to be

probed and prodded with spectral technologies this picture would be the one, as I suspect the portrait might actually depict Will Shakespeare painted from life. I'm also curious about its relationship, if any, to the famous Droeshout engraving from Shakespeare's 1623 First Folio and also to Laurence Hilliard's c. 1620 portrait of Shakespeare.

Over a decade ago I

became interested in a portrait kept in London's Royal Collection said to depict the murdered musician David Rizzio. Four things about the portrait caught my eye:

(1) the sitter's resemblance to the famous Droeshout engraving, (2) the way the portrait's

background contained telltales of having been scrubbed and scamped, (3) the

sitter's familiar looking signet ring, (4) the Shakespearean pate clearly visible inside the full head of hair that hinted the sitter might originally have been painted as bald.

|

| Above: portrait of a man known as David Rizzio (Royal Collection, image via wikicommons) Inscribed

" 'Dad Rizzo MDLXV.' (1565)". Note the opened pocket on the doublet

sleeve exposing bombast, an Elizabethan detail that disappeared from the portrait during its 1974 restoration. |

The Royal Collection does not believe this is a portrait of the infamous fiddler David Rizzio. In fact, they believe the portrait to be Jacobean, not Elizabethan, largely due to its costume, and especially the fountain-fall collar. I agree it's probably not Rizzio but suspect the painting might well be Elizabethan. I also suspect the picture might be a carefully overpainted portrait of Will Shakespeare.

There's plenty of intrigue here. For instance, the 1974 restoration of this portrait eliminated one distinct, and likely Elizabethan, feature of the costume: the sleeve

pocket (worn open with laces or perhaps point-tied fastenings). The sleeve pocket that disappeared was not consistent with the Royal Collection's current c. 1620 dating of the portrait, and now its gone.

Above:

Sir Thomas Drake 1585-93 by H. Custodis. (Weiss Gallery. Buckland Abbey,

Yelverton. Photo source wikicommons.) Note Elizabethan sleeve pocket. Good example of pinking (decorated

with small perforations). Fall or falling collar of linen done in

two layers the top one transparent. Cuffs at wrists. Skirt of doublet a

bit longer.

Minimum shoulder wings with attached bishop style sleeves with pocket.

Peascod bulge

still pronounced. Paneled hose. Hair worn longer.

I find all that very curious, and I've written the Royal Collection about this disappeared pocket and

will update this post when I hear back. (See update below.) I'm curious as to why this sleeve pocket was

eliminated and find it unlikely that some later artist would in-paint an extremely rare Elizabethan-style pocket onto a portrait, especially since the

blue ground of the painting appears to be exposed, perhaps even scraped, all around the sleeve pocket. Was the portrait

x-rayed or IR-ed as part of this 1974 restoration? I'll try to find out. Stayed tuned for the next episode of "The Case of the Disappearing Pocket."

|

| Above:

pocket sleeve with fasteners that are either lacing, or points, or maybe even

hook-and-eye. The entire sleeve pocket vanished during the 1974 restoration of the Called Rizzio portrait (Royal Collection; image via

wikicommons). Note the bluish ground of the portrait, meaning we are

very close to the panel itself. Was this portrait scraped at some point, and, if so, why? There certainly appears to be bombast padding

exposed by the open pocket. Bombast might also indicate the portrait to be

Elizabethan as such padding when out of style by the turn of the

century. |

Above: the portrait called Rizzio before and after its latest restoration. (Image on right from Royal Collection Website and used here under Fair Use Law for comparison purposes). Note how a very unique detail, one that may date the sitter's costume as Elizabethan, has been removed (see below to learn more). Why did they removed the sleeve pocket?

Antonia Graser's 1994 book Mary, Queen of Scots described

David Rizzio as ugly, short, and hunchbacked, so it's fair to wonder if this handsome jack is Mr. Rizzio. Misleading inscriptions are fairly common, after all.

It's worth remembering that

Rizzio was hideously murdered--stabbed 57 times--when his rumored lover, Mary, Queen of Scots, was

six-month's pregnant. Mary's husband Lord Darnley believed, or claimed to

believe, that his wife had been impregnated by Rizzio. Mary's subsequent son, possibly the

bastard love-child of a rank fiddler, would grow up to become Great Britain's King James I, so the stakes are high on this portrait, and Rizzio's possible intersections with the Stewart clan have been largely repressed. Having fiddler blood instead of royal blood makes for an impressive dynastic scandal.

|

| Above:

Called David Rizzio (Royal Collection; image via wikicommons) &

stipple engraving of Rizzio (NPG; image via wikicommons). The original print of the engraving states it was copied from a portrait of Rizzio

painted in 1562 by an

unknown artist "in the possession of H. C. Jennings, Esq." Click here to view the recently restored version of the Called Rizzio

portrait currently on the Royal Collection website. |

The

Royal Collection website makes no mention of the sitter's signet ring when

discussing the costume, but it's odd for a musician to wear such a ring. If this is actually a portrait of Rizzio, perhaps the ring can be explained by Rizzio's quick rise from being a

bass singer in Mary's court to being installed as her Secretary to

France. The matrix or face of the ring appears a bit off-center to me. I'll return to the signet ring later in the update below.

Another enigma about this portrait is that its sitter appears to have originally been

painted as bald. Obviously no artist would paint a

sitter bald and then add hair later; yet we can see clear evidence of the

sitter's pate lurking behind the hair.

|

| Above: detail reveals what appears to be a bald pate that was later

overpainted with hair (Royal Collection, image via wikicommons). The

black hair resembling a dyed comb-over is especially odd since the

darker hair is depicted on the lighter side of the portrait in regard to

the change of color along the background. |

|

Above:

the Marshall portrait of Shakespeare (left, Folger Shakespeare

Library), Called David Rizzio (center, Royal Collection, image from Wikicommons) and the

Droeshout engraving (right, Folger Shakespeare Library).

|

Above: side by side comparison between the Droeshout engraving (reversed) from First Folio show shows eerily similarly lined-up bald pates. The eyes also match up well. Note that engraving were often reversed images of painted portraits; therefore we don't know if the Droeshout engraving is reversed or not.

The background of the portrait appears to my eye heavily scamped in the areas likely to have inscriptions (and yes in the update below the Royal Collection confirms the portrait's background is heavily overpainted but apparently they made no effort to remove this overpaint when retouching the portrait's sleeve pocket).

As to this fountain-style fall collar, said to be Jacobean, it also shows up in the history of bard portraits in the miniature

of Shakespeare attributed to Laurence Hilliard. Once again we see a strong physical resemblance between the two sitters. Whoever this unknown jack is, he greatly resembles Laurence Hilliard's William Shakespeare.

|

| Left: copy of the Laurence Hilliard (c. 1620) miniature of Shakespeare by TW Harland (left, National Portrait Gallery, London). Right: portrait called David Rizzio (Royal Collection). See any resemblance? | | |

|

Finally, for the benefit of our Oxfordian readers, here is a comparison of

the Rizzio portrait with Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, who was considered an excellent musician

and played multiple instruments. Many authorship skeptics believe de Vere to be the true author of Shakespeare's plays. To this I will only add that the violin originated in the early to mid

16th century in Italy and migrated from Italy to England.

|

| Above left:

the Welbeck portrait of Edward de Vere (Welbeck Abbey, image from

wikicommons). Above center: Called David Rizzio (Royal Collection, image from

wikicommons). Above right: c. 1987 post-cleaning photo of the

controversial Ashbourne portrait (Folger Shakespeare Library, right). |

|

| Above:

hand with signet ring from the Ashbourne portrait (left, Folger

Shakespeare Library) & hand with signet ring from Called Rizzio

(Royal Collection). |

Oxfordians have been convinced for decades, and with good reason, that the Ashbourne portrait had its Elizabethan collar

overpainted in order to misidentify the sitter Edward de Vere as a haberdasher named Hamersley. Could this inscribed Rizzio portrait actually depict the young Edward de Vere with his violin? Or is this instead a Jacobean portrait, which would mean its sitter is neither de Vere

or Rizzio?

A big clue to the identity of sitter might lie in the signet ring, and it would be interesting to probe this ring with spectral technologies. After all, the whole purpose of signet rings is to identify the sitter's family. . .

So, lots of red flags here. And lots of reason to x-ray, or infra-red, or use whatever occult technologies have cooked up of late to get under the paint. Expect some updates to this posts.

Update.

I have now received a number of emails from the Royal Collection about their called-Rizzio portrait. Perhaps the most important reveal is that all the conservation notes from the portrait's 1974 restoration (its only restoration of note) have been, well, um, lost. (This is almost invariably the case with Shakespeare candidate portraits btw.) The sleeve pocket was presumably removed, I learned, because it had been added to the portrait, but there's no mention in the email of how that was determined or if x-rays or IRs were even employed. One email implied the sleeve might have been added to make the portrait appear Elizabethan, though it's unclear why anyone would want to forge a portrait to depict David Rizzio.

Also the emails from the Royal Collection makes it clear that I was correct about the background of the portrait being overpainted. The Rizzio inscription was also added to the portrait at a later date. Apparently the doublet is not leather, though it certainly looks like leather to me. A letter in the portrait's file once described the portrait as a "problem picture." I would agree.

Below are the emails I received from the Royal Collection. I've highlighted certain passages in bold print. For example, I highlighted the passage in one email in which, within the same paragraph, I was informed that sleeve pockets never existed, and then I was told that maybe the sleeve pocket was added to make the portrait appear Elizabethan. If sleeve pockets didn't exist, then how could one have been added to make a portrait appear Elizabethan?

Also note I immediately responded to that email by sending them a photograph of an Elizabethan portrait with a sleeve pocket (see below portrait of Horace Vere).

As you read these emails, ask yourself why the Royal Collection has not explored this "problem portrait" with x-rays or infrared light etc. After all, they admit it's extensively overpainted. Obviously somebody went a lot of trouble to misidentify the sitter. Why not learn the portrait's true history? I just don't understand the lack of curiosity in certain collections. And let's bear in mind there's a signet ring here that the Royal Collection knows has been overpainted to deceive us, and yet they've made no effort to test that ring to see its original signifying matrix that will tell us who this person is. Why? What is the Royal Collection they afraid of?

Dear Mr Durkee,

Thank you for your e-mail regarding the

Portrait of a Man known as David Rizzio in the Royal Collection

(RCIN 401172). The image that you saw on our website (now no longer

visible) dates from 1971. It was taken prior to conservation, which I

understand took place in 1974 and appears to have

been overseen by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (SNPG).

According to a letter of 1988, in our files, correspondence with the

conservator who worked on the painting and the SNPG are missing. I

suspect that it was during the conservation that the pocket

sleeve and lacing were removed presumably because they were identified

as later overpainting.

The painting is due to be published in a revision of Oliver Millar’s

Tudor, Stuart and Early Georgian Pictures, 1963 (although it was

not included in the first edition). It is thought that the background of

the painting has been extensively overpainted. The inscription (which

gives the date of the portrait as 1565) is

not original and was presumably added a number of years after the

portrait was painted. The costume of the sitter can be dated to

c. 1620 on the basis of the falling ruff which is far too large for a portrait of the mid-16th

century as well as the shape of the doublet, particularly in terms of

the manner in which the shoulder wings project beyond the arms. The

style

of beard and hair are also much more like the fashions of the 1620s.

Perhaps

the overpainted ‘pocket’ in the doublet was an attempt to make it

appear more Elizabethan. It may also have been a misinterpretation of

the fashion for paned (slit) sleeves on

doublets, which were common around 1620. Pockets were never found in

this sleeve location. The way in which the fabric of the garment has

been painted seems more indicative of wool or silk rather than leather

and it would have been known as a doublet not a

jerkin as jerkins were sleeveless.

In

a letter from Dr Duncan Thomson, then Assistant Keeper of Art, SNPG, to

Robert Snowden, the conservator, he describes it as a ‘problem picture’

and felt it was wrong to call it a picture

of Rizzio.

You

may be interested to know that there is a mark impressed on the

stretcher of the painting from the firm of liners, John Peel (c.1785-1858).

I hope this information is of interest.

My reply to the Royal Collection (below):

Thank you for the

helpful reply. I still have a few questions and am sorry to hear the

notes on the conservation have been lost. Were any spectral tests done

on the portrait prior to its restoration? I'm curious as to how it was

decided the pocket was added, especially since it was so unique. And

thanks also for confirming the sleeve pocket used lacing--I wasn't

positive--and yes that would certainly make it Elizabethan.

I

disagree that sleeve pockets were never located in that general area

and am attaching a portrait to support my case. I have to say it's

awfully strange for somebody to in-paint such a specific and uniquely

laced open pocket onto a portrait--I've never once seen a laced pocket

depicted as open, so it's hard to believe they copied it there from

another portrait. And that appears to be bombast that's exposed by the

opened pocket, too, and of course bombast disappeared by the end of the

century as the human figure returned to men's fashion following

Elizabeth's death. To my mind, the argument that somebody wanted the

portrait to depict Rizzio so badly they painted an Elizabethan pocket

onto the portrait is as strange as an argument stating a fall collar was

overpainted onto the portrait to make it look Jacobean. Neither

argument has much logic behind it and with the conservation notes

lost--you'd be surprised how often this is the case--I guess we will

never know now, which is a shame.

Please

do let me know if any x-rays or IRs were taken. Or if there are any

alternative routes to learning more about this portrait's

conservation--might records exist elsewhere?

Thank you again for the reply and this information,

Lee

Above: portrait of Horace Vere, 1594 (image from Wikicommons). Note the pocket sleeve, stuff with bombast, clearly visible in the exact location of the portrait known as David Rizzio. The pocket sleeve was therefore an Elizabethan detail and might well date the portrait known as David Rizzio to c. 1594.

Email reply (below) from the Royal Collection in which my evidence the side pocket was an Elizabethan style goes oddly un-noted as does my argument no painter would have forged this obscure costume detail onto a portrait:

Dear Mr Durkee

Thank

you for your e-mail and apologies for the delay in replying. I have now

traced the correspondence and reports on the painting from its

time at Stenhouse

Conservation

Centre during the 1970s and I am afraid that there are no references to

any X rays or technical analysis of the painting. There

is also no discussion of the removal of the laced pocket sleeve. There

is, however, reference to removal of areas of ‘inpainting’ (later

overpainting) in ‘oil colours’ which I presume relates to the pocket.

I

can only re-iterate that Dr Duncan Thomson, Assistant Keeper of the

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, (who oversaw the conservation)

believed

that it was wrong to go on calling it a portrait of Rizzio. He felt

the costume of the sitter can be dated to c. 1620 and the style of the

portrait are of about the same date. I am sure you are aware of the

almost-half-length engraving by Charles Wilkin

(c. 1759-1814), of Rizzio, in a ruff and cap, and playing the lute. The

engraving is presumably after a portrait of Rizzio which is now not

known, and was published by Robert Triphook in 1814 (British Museum). We

believe the violin in our portrait could possibly

date from the early eighteenth century, however it appears to be an

inauthentic rendering of an instrument of the period.

Finally,

I attach a detail of the pocket sleeve from a photograph taken in 1971,

prior to the conservation, and we would welcome any further

thoughts that you have.

With kind regards [. . .]

.jpg)

.jpg)