Thursday, April 27, 2023

Friday, April 14, 2023

Oxford University, Edward de Vere, and the Stratford Bust: Is This the Smoking Gun of Shakespeare Studies?

Above left: The Welbeck portrait of Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford (owned by Welbeck Abbey, image from Wikicommons). Above right: the Hunt or Stratford portrait of Shakespeare (owned by Stratford Birthplace Trust, public domain photograph from 1864).

This post picks up where my book STALKING SHAKESPEARE leaves off following its chapter on why the Hunt portrait of Shakespeare has a strong claim to Shakespeare ad vivum (painted from life) and was quite likely the template portrait used to create the iconic bust of Shakespeare in Trinity Church.

Above: the Stratford bust next to the Hunt portrait of William Shakespeare (both photos from Friswell's 1864 Life Portraits of William Shakespeare). In both likenesses Shakespeare is wearing a red jerkin beneath a black robe. No scholar as ever disputed the connection between the two artworks, but which came first?

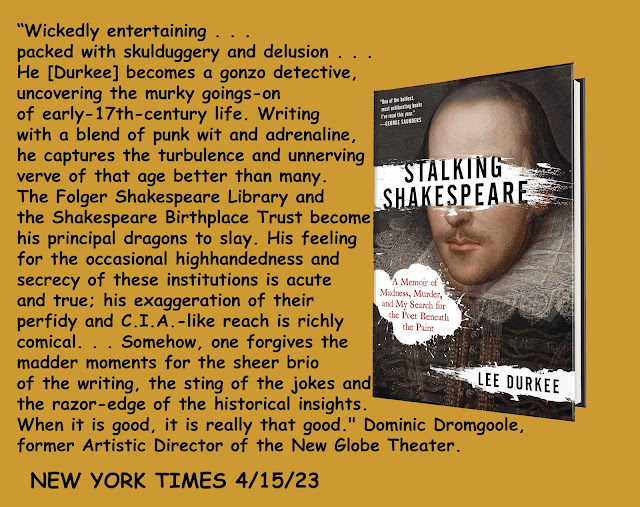

STALKING

SHAKESPEARE is not an authorship book. It's a memoir about my unruly

obsession with identifying unknown courtiers in Elizabethan and Jacobean

portraits. But the book does delve into the authorship debate whenever that

controversy overlaps my portrait obsession (such as with the infamous Ashbourne portrait of Shakespeare) and I do my best to remain a neutral.

The Hunt portrait of Shakespeare is fascinating beyond measure and plagued with telltales scandals--for example, the portrait was discovered in a Stratford attic in the mid-19th century purposely disguised so as not to resemble Shakespeare; yet when cleaned with solvents the portrait turned out to be the spitting image of the famous town bust. No scholar has ever disputed the intimate connection between the portrait and the bust, which leaves us with two logical scenarios: either the portrait was used to create the bust or the bust was used to create the portrait.

STALKING SHAKESPEARE takes up the claim by 19th century scholars that the portrait came first and was used to create the bust, and my book also argues the Hunt portrait needs to be tested by its owners at the Stratford Birthplace Trust. Because of their neglect, we don't know how old the portrait is or what lies beneath its overpaint (and we know via multiple expert testimony that the picture was immediately altered after its discovery, although we don't know why or to what degree it was altered). As to its age, the portrait descended from the aristocratic Clopton family collection in Stratford and had been stored in the Hunt family attic for at least a hundred years when it was discovered in 1860.

Now let's return to the famous bust at Trinity Church and ask ourselves whether or not that bust could be a tribute to Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford?

We know that the traditional Shakespeare of Stratford (the businessman/actor) was not a college-educated man and that there's no record of him even attending the local grammar school in Stratford. With that in mind, it's interesting that a traditional scholar is now conceding that the Stratford bust (and by extension the Hunt portrait) depicts Shakespeare wearing an Oxford University gown.

Lena Cowen Orlin, a professor at Georgetown University, has made this argument inside the pages of The Guardian that states:

The figure is wearing an Oxford University undergraduate’s gown, and the cushion detail is found in monuments memorialising lives of distinction in its college chapels.

She [Orlin] said the fact that he [Shakespeare] wanted to be memorialised with links to the university – despite never going to university himself – “now suggests some collegial association that we don’t know about”.

I'm not sure Orlin's logic holds up in the second paragraph, but the important point is that Shakespeare was immortalized wearing an Oxford gown when we know--and Orlin concedes this--that the traditional author did not attend Oxford. This is quite the monkey wrench tossed into the traditional narrative.

The first question that arises is why did it take centuries for scholars to figure out Shakespeare was wearing a gown that attached him to Oxford University? I would suggest that confirmation bias played a large role, which might also explain why this revelation came out of an American university instead of one in England such as, well, hmm, Oxford.

Edward de Vere, long rumored to have written the works of Shakespeare, did in fact attend Oxford University (hardly surprising for the 17th Earl of Oxford). Clearly the last thing traditional scholars want to do is connect their iconic bust to that infamous earl they despise.

But there's another type of confirmation bias at work here, I suspect, and this one can be found rooted inside the de Vere authorship camp which seems hellbent on denying any connection between their hidden author (de Vere) and the two most famous likenesses of Shakespeare: the Stratford bust at Trinity Church and the Droeshout engraving from Shakespeare's 1623 First Folio. The de Vereians vehemently want those two iconic likenesses to be red-herring representations of the actor/businessman they believe was used as a mask for the the real Shakespeare.

By contrast I think, within the Oxfordian framework, it begs to be argued that one or both of these two traditional likenesses (the bust and the engraving) were created, as much as possible within imposed limitations, to celebrate Edward de Vere. The physical similarities in the photographic comparison at the top of this post seems to my eye more than coincidental and raise questions that are never going to be answered as long as both camps keep their religious blinders on.

If I were an Oxfordian, the question I'd be asking right now is: has Shakespeare been hidden from us in plain sight?

Related links:

https://lostshakespeareportraits.blogspot.com/2019/10/a-curious-portrait-of-man-stabbed-57.html

Note: all photographs in this post are used for identification purposes under Fair Use laws. I apologize for not using a color photograph of the Hunt portrait, but the Stratford Birthplace Trust does not make these available.

Saturday, March 25, 2023

Monday, August 29, 2022

DOES THIS PORTRAIT MINIATURE DEPICT THE FAIR YOUTH 3RD EARL OF SOUTHAMPTON?

This beautiful portrait miniature, kept in London's excellent Victoria & Albert Museum, was for years identified on that museum's web page without caveat as a portrait of Sir Philip Sidney painted by Isaac Oliver. I do not think this is a portrait of Sir Philip Sidney nor do I think the painter Oliver; instead, I suspect this to be a portrait of Shakespeare's beloved Fair Youth 3rd Earl of Southampton Henry Wriothesley.

My frustrations with this miniature began many years ago when, trusting the V&A's identification of the sitter as Sidney, I started using the miniature as a template to help me identify other possible portraits of Sidney. Bear in mind, I have an odd infatuation with Sidney, a courtier I don't particularly like yet find enigmatic. Two enigmas associated with Sir Philip that grate me: (1) throughout his short life Sidney was treated with the godly reverence due a royal heir, and (2) although he was at the center of the Elizabethan portrait revolution, only one authentic painted portrait of Sidney has survived.

British museums hoard their photographs of public-domain portraits by pretending these rote photographs are works of art in themselves. These museums seldom share high-resolution photographs nor will they let authors use these rote photos without first purchasing expensive permissions. Due to this hoarding of public-domain images (I won't pretend to hide my disgust) I was unable to obtain a high-quality photograph of the miniature the V&A web page described as Sir Philip Sidney painted by Isaac Oliver.

Then one day, irritated with my low-res image of the portrait miniature, I held my magnifying glass directly to my computer screen and realized, within moments, the so-called Sidney miniature had likely been altered via both extirpation and overpaint.

The first anomaly to catch my eye was the misshapen "I-O" monogram of the artist Isaac Oliver. This monogram appeared slipshod in comparison with other Oliver monograms I'd seen. Something was wrong here, I felt.

Suspicions roused, I next noticed what appeared to be vestiges of an inscription along the upper background. Was it my imagination or had an inscription been scrubbed from the portrait miniature? Inscriptions, bear in mind, can be vital in identifying painters. A Nicholas Hilliard miniature can be identified by Hilliard's unique style of calligraphy, as can a Hieronimo Custodis portrait. While staring into this seemingly ghosted inscription, I even began to wonder if this might be an invaluable Hilliard portrait miniature that somehow got misidentified inside a private collection.

That was hopeful thinking, I'll admit, but it did seem unlikely to me that such as prestigious figure as Sidney would have been painted, face and all, by Hilliard's then-apprentice Isaac Oliver. As Elizabeth Goldring pointed out in her excellent Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist, Sidney and Hilliard were friends and enjoyed discussing the relationship between poetry and paintings inside their vaulted Areopagus Society. Would Hilliard have allowed his apprentice to paint such a dignitary as Sidney?

Well, if Oliver did paint the miniature, I reasoned, then the miniature was likely a copy of a Hilliard original.

As I kept wanding my magnifying glass across the computer screen, I soon noticed a mask of white overpaint marring the

sitter’s forehead. Odd, I thought. And there were other spots that looked patched over as well. Later the V&A would confirm to me in an email (see lower post) that overpaint had been applied not only to the sitter's forehead but also to his hair and hand.

At this point I was still trusting the V&A identification of the sitter as Sir Philip Sidney; and yet this sitter bore only a passing resemblance to the long-faced sitter in Sidney's one authenticated painted portrait.

Below left: NPG 2096 c.1578 Sir Philip Sidney (artist unknown, image from Wikicommons). Below right: the V&A miniature once said to be Sidney. Obviously these two sitters don't much resemble each other.

Finally I took a closer look at the sitter's costume, and that's when things got fascinating (well, to me, at least). The miniature's red-haired sitter was sporting a half-mast linen lawn collar trimmed with Italian cutwork (called reticella, I believe). This collar was likely raised off the shoulders by a hidden rabato wire system. Such collars did not come into fashion until years after Sidney’s 1586 death when fashion began to relax, and ruff, peascod, and bombast vanished from the scene.

Wrist ruffles disappeared almost entirely around 1583 when cuffs came into fashion. Yet the sitter in the mystery miniature is clearly sporting cuffs.

Sidney was born in 1554 and died in 1586. If we assume the sitter in the portrait to be around twenty years old (give or take) that would set this portrait c. 1574. But the collars of that period were nothing like the one in the miniature. The collars of the 1570's were tall standing collars. Furthermore, according to Ashelford, collars did not become separate items of clothing until the mid 1580's.

In short, costume dating all but eliminates the possibility of the sitter being Sir Philip Sidney. The costume doesn't fall within Sidney's life span. And if the portrait was painted right before Sidney's death in the early 1580's, then Sidney, a renowned clothes horse, would likely have been wearing a giant cartwheel collar above a bombast-stuffed doublet with giant buttons and a peascod-bellied doublet with a cloak thrown as if carelessly over the left shoulder.

So if it's not Sidney, and it isn't, then who could it be?

Above: mystery sitter from V&A miniature (left) and a miniature of Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, by Nicholas Hillard (V&A Museum, image from Wikicommons).

Above: mystery sitter from V&A miniature (left) and another miniature of 3rd Earl of Southampton from Albion Collection (image via Bonhams auction website). Please note that both sitters have notably large heads in relation to their small torsos. Also note the shoulder wings of the doublets are identical. The similarities of the collars are obvious as well. The ears are consistent both in location and shape, as are all other facial features.

Eventually I emailed the Victoria & Albert with some questions, and their quick reply set my head spinning. Apparently my email had caused the museum to change their online identification of the miniature almost overnight. The sitter was no longer Sir Philip Sidney but "possibly Sir Philip Sidney" and the painter was no longer Isaac Oliver but "after Oliver" (indicating a copy of an Oliver miniature).

The V&A email not only admitted their identification of Sidney “is possibly suspect, as you yourself have also suggested,” but also described the painter’s “I-O” signature as “probably spurious . . . likely to be a later addition.”

The museum blamed their mistake(s) on a computer update, but I had been using this portrait as a template for years and knew that this was no recent error.

Below is the email I received from the V&A.

Dec. 11 2019

Dear Lee Durkee

Thank you for your enquiry about the supposed portrait miniature of Philip Sidney (museum number 630-1882). As I mentioned in my reply to your previous enquiry, time has been allocated from January to end March 2020 to update and ‘clean’ the online entries for the V&A’s collection of Tudor and early Stuart miniatures. This will include some new research undertaken during 2019 for the anniversary of Hilliard’s death, especially for the exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London. But it will also involve ‘cleaning’ up existing entries as it seems that a recent computer update has resulted in certain fields in a curator’s original catalogue entry failing to transfer to ‘Search the Collections’ (STC) – the museum’s public-facing cataloguing.

In the case of 630-1880 I have just made a few quick updates which should go ‘live’ overnight, to move information to fields which can be seen by the public. These reflect the fact that the miniature has long been catalogued as ‘after’ Isaac Oliver, that the ‘IO’ signature is likely to be a later addition, and that the description of the sitter as ‘Philip Sidney’ is found on the back of the 19th century frame, and is possibly suspect, as you yourself have also suggested. A museum catalogue entry from 1923, which was originally cited in full in my online cataloguing, comments: “The frame is 19th century work. The miniature is a 17th century production, but most probably a copy after Isaac Oliver. Though the hand, collar and dress are drawn with vigour, there is weakness in the face and hair. The miniature has been retouched on the background and probably on the back of the hand; the forehead has been almost entirely repainted. The signature is probably spurious; it is painted with a different gold from the ear-rings and the border.” I have only partly transferred this information to STC as I should examine the miniature myself in the new year.

Further amendments could be made from January to March 2020 as this and some other miniatures will have to be physically re-examined. Any new or corrected information will be added to the record and will go ‘live’ on Search the Collections and available to the public as each entry is signed off.

Yours sincerely

Katherine Coombs

Curator, Paintings

Ultimately we are left with three questions (1) who painted this excellent miniature? (2) who sat for it?, and (3) why is an ex-cabdriver in Mississippi the only the person who cares?

My guess is the portrait depicts Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. I think a study in costume would support this suggestion (and would certainly eliminate Sidney). I also find it quite the coincidence that mystery sitter in the miniature struck the identical pose (right hand over heart) found in one of Southampton's early portraits. In the below comparison, please note the similarities of the collars, the earrings, the hair line, the face and ear shape, and the hands.

Above: unknown sitter from V&A miniature (left) and portrait of Henry Wriothesley (Collection of Alex Cobb; image from wikicommons). Again note the similarity of the collars. Although the hand has been overpainted in the V&A image, it still bears a great resemblance to young Southampton's.

Other civilized countries make high-resolution images of their historical portraits available to the public. Other countries allow author to use photographs of public-domain portraits without buying expensive permissions. (For example, the excellent Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC provides high-resolution photographs of their Shakespeare portraits to anyone who visits their web site and charges absolutely nothing for permissions.) These are public-domain images--meaning the public owns them. It's time Great Britain caught up with the rest of the curatorial world and changed their self-serving policies. These photographs they are hoarding are not works of art. They are simple photograph any robot could take.

FYI, anyone interested in Fair Use laws regarding public domain images of portraits should consult this excellent website from the Center of Media & Social Impact.

Related Links: How To Date Elizabethan Portraits By Costume: Men's Portraits

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

My Novel THE LAST TAXI DRIVER Splashed Across Front Page of Le Monde's Weekly Book Review

In my wildest dreams I could never have imagined this happening. Very grateful to my French translator Nicolas Richard for landing me on the front page of Le Monde's weekly book review.

Friday, February 15, 2019

Does This Stunning Portrait Miniature by Nicholas Hilliard Depict Spain's King Phillip II?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Museum Stockholm unknown man 1583 by Nicholas Hilliard |

|

| (left) the Stockholm Hilliard (right) portrait called Philip II from Bridgeman Images |

Word of caution: it's entirely possible the Bridgeman portrait has been misidentified as Philip II. Yet there are reasons to suspect the Hilliard miniature does depict the Spanish king, via a greatly beautified version, which was Hilliard's trademark. "Leave out the shadows," Elizabeth once warned him.

In his essay "Faces of a Favorite," Sir Roy Strong stated that mass-producing portrait miniatures for gifts was a prerogative exclusive to royalty, "an act of a sovereign." With that in mind, this miniature might present Philip II and not some "unknown nobleman" as it's now designated. The low quality of the studio copy does make it appear to be a product of mass production.

The inscription, or motto, is Italian. "Non poco da Chese medessimo dona" translates into the wittism, "He who makes a gift of himself gives not a little."

The quality of the Stockholm miniature indicates it was an important piece with a royal blue background. The museum catalogue states: "On the reverse [of the miniature] is a representation of the Crucifixion, with a costly rock-crystal mount reminiscent of the reliquaries of earlier ages."

|

| Philip II of Spain after Titian photo National Portrait Gallery London |

So is it Philip? The incredible NPG portrait of Philip (above) certainly bears a strong resemblance to the miniature's sitter. I'll post some side-by-side comparisons soon.

.jpg)